Reporting and responding to child wellbeing and safety concerns

Protecting children from harm is a responsibility shared by everyone in the community. Making a report about suspected child abuse or neglect is an important part of this responsibility.

Overview

Protecting children from harm is a responsibility shared by everyone in the community. Making a report about suspected child abuse or neglect is an important part of this responsibility. Any member of the community can make a report by calling the Department of Communities and Justice (DCJ) Child Protection Helpline (the Helpline), or by walking into a local Community Service Centre, if they suspect on reasonable grounds that a child or young person is at risk of significant harm (ROSH).

In NSW selected classes of people, known as ‘mandatory reporters’, are required to report suspected child abuse to government authorities. Mandatory reporting requirements are included in the Care Act and theChildren and Young Persons (Care and Protection) Regulation 2012.

Mandatory reporters from NSW Police, Department of Education, and NSW Health are required to report child wellbeing concerns to their Child Wellbeing Unit (CWU).

This Part includes the following topics:

- Reporting framework

- Mandatory reporting

- Making a report

- Safeguards for reporters

- Reporting child abuse to the police

- Responding to child wellbeing and safety concerns

- Practice advice and resources

Reporting framework

DCJ is the agency responsible for receiving and assessing reports about a child being at Risk of Significant Harm (ROSH).

Reporting a child at ROSH

Any person who has reasonable grounds to suspect that a child or class of children is at ROSH should make a report to the Helpline or a Child Wellbeing Unit (CWU) if one is available to them.

Before reporting a concern, mandatory reporters are encouraged to contextualise their concern within the child’s culture. Many cultures have child-rearing practices which differ from Anglo-Australian ways to raise children. For example Aboriginal child-rearing practices favour the child learning to be safe through exploration of their local environment.

Aboriginal cultures also view child-rearing responsibility to belong to the wider family, the kinship network and the community. Because of this, Aboriginal children may be out without a parent present whilst being supervised by the many communal eyes watching over them. It is important to consider different cultural practices when making an assessment of child safety.

What is ROSH?

Subject to section 23 of the Care Act, a child or young person is at ROSH if the circumstances that are causing current concerns for the safety, welfare or wellbeing of the child are present to a significant extent.

Concerns that may constitute ROSH include the following:

Neglect - a failure by a person to provide adequate and proper food, supervision, clothing, medical care or lodging for the child that causes or is likely to cause harm to the child. In the case of a child who is required to attend school, parents or care givers not arranging for a child to attend school can be neglect. Not providing for a child’s psychological needs can also be neglect.

Sexual abuse - any act which exposes the child to, or involves them in, contact or non-contact sexual activity that results in harm, or is likely to result in harm, to the child. Child sexual abuse can be perpetrated by an adult, another child or a group. N.B: Age or developmentally appropriate peer consensual sexual activity may not be sexual abuse. The Mandatory Reporter Guide (MRG) provides further guidance on what is considered problematic, abusive or inappropriate for age and development, and what action to take.

Physical abuse - any non-accidental physical act inflicted upon a child which has the potential to injure the child, with or without the presence of external injuries.

Emotional abuse, psychological harm or ill treatment - any act by a person that results in a child suffering any kind of significant emotional deprivation or trauma.

Domestic violence - the child is living in a household where there have been incidents of domestic violence and as a consequence the child is at risk of serious physical or psychological harm.

Family violence - The term family violence (preferred in many Aboriginal communities) is broader than the usual mainstream definition. Family violence involves any use of force or coercion, be it physical or non-physical, which is aimed at controlling another family or community member and which undermines that person’s wellbeing. It can be directed towards an individual, family, community or particular group.

Concerns for risk of harm may relate to a single act or omission or to a series of acts or omissions.

For more information on child abuse and neglect and how to respond when a child or adult tells you about abuse, see What is child abuse and neglect?

For practice tips to support the detection of different types of harm and risk of harm and other topics, see Risk Specific Practice Support.

Find general resources, tools and training for child protection practitioners here Caseworker resources and tools.

Signs of abuse and neglect

There are common physical and behavioural signs that may indicate abuse or neglect. Examples of many signs can be found on the DCJ webpage on possible signs of abuse and neglect.

Neglect

Signs of neglect which may be seen in children can include:

- Low weight for age or significantly above a healthy weight, or is not receiving appropriate nutrition

- Untreated, or inappropriately treated medical or mental health condition

- Child appears extremely dirty, or is wearing clothing that is not appropriate for conditions

- Parent/carer is not attending to the child/young person’s personal hygiene needs

- Child is living in a dangerous environment

- Inadequate supervision for the child’s age

- Scavenging or stealing food

- Poor school attendance or lack of school enrolment

- A parent is indicating they wish to relinquish the care of their child

- Isolation from other children

The parents of children experiencing neglect may show a limited understanding of the child’s needs or difficulties meeting those needs.

Physical abuse

Signs of physical abuse which may be seen in children can include:

- Bruising or marks which may show the shape of an object (e.g. belt or hand print)

- Lacerations and welts

- Explanations of injuries which are inconsistent with the injury

- Illnesses in children that are unexplained and may have been inflicted e.g. intentional poisoning

Emotional abuse or psychological harm

Signs of emotional abuse or psychological harm which may be seen can include:

- Suicide threats or attempts

- Persistent running away from home

- Taking extreme risks, including being markedly disruptive, bullying or aggressive towards others.

- The known presence of domestic violence, a parent/carer’s poor mental health and/or a parent/carer’s substance misuse or abuse with impact on the child

- Domestic violence is suspected based on observations of extreme power or control dynamics (including extreme isolation) or threats of harm to adults in the household

- A child is a danger to self or others as a consequence of parent/carer behaviour

- An underage marriage or similar union has occurred or is being planned

Sexual abuse

Child sexual abuse occurs across all cultural and socioeconomic groups, genders and ages. However, several studies have shown that offenders target children and families who have certain characteristics and are already under stress, marginalised, and experiencing vulnerability. The abuse is generally perpetrated by someone the child or the child’s family knows (it can be another child, neighbour, caregiver, relative or immediate family member).

‘Grooming’ is often used to describe behaviour by the offender towards the child, their family and their community. The behaviour is focused on increasing opportunities for sexual abuse to occur, reducing the child’s ability to tell others what is happening, and creating barriers to the child being believed if they do disclose.

Disclosure in child sexual abuse is rarely a spontaneous event and it is more likely to occur slowly over time as part of a process. Sexual abuse against children is a crime.

Signs of sexual abuse which may be seen in children can include:

- Disordered eating or preoccupation with body

- Change in dress and/or a desire to cover up

- Excessive compliance or a desire to be overly obedient

- Poor self-image, poor self-care, or lack of confidence

- Persistent sexual themes in drawing, stories and play

- Regressive behaviours (e.g. soiling or urinating in clothing)

- Running away, recklessness, suicide attempts or self-harm

- Sexual behaviour or knowledge that is advanced or unusual

- Sleep disturbance, fear of bedtime, nightmares, or bed wetting

- Not wanting to be left alone with a particular individual/s

- Unexplained accumulation of money or gifts

- Unusual or repetitive soothing behaviours (e.g. hand-washing or pacing)

- Difficulty concentrating, memory loss or decline in school performance

- Inappropriate sexual play with themselves, other children, dolls or toys.

Problematic sexual behaviour and harmful sexual behaviour

Sexual knowledge or behaviour that is inappropriate for a child or young person’s age may be a possible sign of sexual abuse.

Problematic sexual behaviour (PSB) describes behaviour of a sexual nature outside the range accepted as ‘normal’ for a child’s age and level of development. Harmful sexual behaviour (HSB) is when a child may use their power, authority or status to engage another child in sexual activity that is unwanted or where the other person is not capable of giving consent. Harmful sexual behaviour may also be a possible sign of sexual abuse, and may also be an indicator that the child exhibiting the behaviours have themselves been the victim of violence, abuse or neglect.

Determining “harm” experienced by any child must always encompass a broader consideration of all children’s overall emotional, physical, psychological, and relational, development and wellbeing.

The spectrum of harmful sexual behaviours and the diversity of children’s backgrounds and circumstances mean that no one response or intervention is suitable for all children displaying problematic or harmful sexual behaviours. A range of interventions is needed, from prevention and early identification, through to assessment and therapeutic intervention. For a small group of children, a child protection or criminal justice response may be necessary.

The True Traffic Lights resource provides a guide to assist those working with children to identify the characteristics of a child’s sexual behaviour, and then to understand and respond to the behaviours in a way that is appropriate and supportive based on the behaviours identified.

New Street Services provide therapeutic services for children and young people aged 10 to 17 years who have engaged in harmful sexual behaviours. New Street Services work with the young person to assist them to understand, acknowledge, take responsibility for, and cease, the harmful sexual behaviour.

Children under 10 years who display problematic or harmful sexual behaviour can be referred to NSW Health Sexual Assault Services for therapeutic intervention.

NSW Health Sexual Assault Services provide a response to children under the age of criminal responsibility who have engaged in problematic or harmful sexual behaviours. This response may involve delivering therapeutic supports, or may involve case management and warm referrals into another service delivering these supports.

See, understand and respond to child sexual abuse - A practical kit gives practitioners a broad understanding of child sexual abuse, including the impact of sexual abuse on children. It also provides practical guidance for practitioners to see, understand, and respond to, child sexual abuse where abuse is disclosed or suspected, but not confirmed.

Helping to Make it Better, is a user friendly information package addressing the questions commonly asked by parents, and provides information about the nature of child sexual assault and some possible effects on children and families. Also included is practical information about how parents can assist and support their children in the aftermath of sexual abuse. Information is provided about the services that are involved after child sexual assault is reported to the Department of Communities and Justice Services. It explains ways in which sexual assault services can assist parents and children. The updated edition includes two new information sheets. One is for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander families. The other is for when your child has been sexually assaulted by a child.

Nothing But the Truth, is a resource that is designed to provide workers with the information they need to ensure victims of sexual assault receive accurate and accessible legal information through a process that is empowering, culturally safe and supportive.

Mandatory reporting

Who are mandatory reporters?

In NSW, mandatory reporting obligations apply to those who deliver the following services wholly or partly to children as part of their professional work or other paid employment. It also includes those in management positions in organisations that deliver these services:

- Health care (e.g. medical practitioners, specialists, nurses, midwives, occupational therapists, speech therapists, psychologists, dentists and other allied health professionals, whether employed privately or by NSW Health)

- Welfare (e.g. social workers, casework practitioners or refuge workers)

- Education staff (e.g. teachers, counsellors or principals)

- Disability (e.g. disability support workers and personal care workers)

- Children’s services (e.g. child care workers and family day care)

- Residential services

- Law enforcement (e.g. police).

People in religious ministry, people who provide religion-based activities to children and registered psychologists are also mandatory reporters.

For more information on mandatory reporters, see section 27 of the Care Act.

When are mandatory reporters required to make a report?

A mandatory reporter must make a report when they have reasonable grounds to suspect that a child is at ROSH and those grounds arise in the course of, or from, their work or role. A mandatory reporter has a duty to report, as soon as practicable, the name or a description of the child, and the grounds for suspecting that the child is at ROSH.

It is important to note that mandatory reporting requirements only relate to children, not young people.

The Mandatory Reporter Guide (MRG)

The online MRG assists mandatory reporters to:

- Determine whether a report to the Helpline or CWU is needed for concerns about possible abuse or neglect of a child or young person.

- Identify alternative ways to support vulnerable children and their families, where a mandatory reporter’s response is better served outside the statutory child protection system.

Applying the MRG before making a report, including referring to the definitions, helps users to identify the key information to include in their report, and to report only matters where ROSH is suspected. Mandatory reporters should complete the MRG, referring to the definitions on each occasion they have risk concerns, regardless of their level of experience or expertise. Each circumstance is different and every child is unique.

After selecting a decision tree representing the risk type that best represents the concern for the child/young person, mandatory reporters are asked a series of questions. At the end, a decision report is provided outlining what to do next. The MRG outcome options are:

- Immediate report to the Helpline - Call 132 111 (you cannot e-Report for this MRG decision)

- Report to the Helpline (in the next 24 hours)

- Refer to CWU or consult with a service/professional

- Referrals

- Document and continue relationship/monitor.

Consult with your CWU, if you have access to one, at any time during completion of the online MRG.

Mandatory reporters are encouraged to complete the MRG for more than one harm type, particularly when they have more than one significant concern.

Where the MRG indicates the level of risk does not warrant a report, the MRG assists mandatory reporters to respond appropriately to children by providing guidance on other possible options to assist the child and their family.

Making a report

How to make a report

If a child or young person is in immediate danger phone Triple Zero immediately.

Reporters can report matters to the Helpline by:

- Phone: 132 111

- eReport through the Child Story Reporter website (requires registration).

Before making a report to the Helpline it is important to have as much essential information as possible. The detail and quality of the information provided is critical to the quality of the decision making that follows. When making an eReport, it is important to provide comprehensive evidence which includes a detailed description of direct observations that indicate a child may be at ROSH.

If possible, reporters should have following information ready when making a report:

- Information about the child, including: their name, address, date of birth or details about their family/significant others

- Details of the ROSH (such as the date, type of risk, detailed observations, details of person/s causing or contributing to the significant harm)

- Impact of the incident on the child

- Network of supports around the child

- The reporter’s details, including call back information

You should find out if a child is, or may be, Aboriginal so that the specific protections under the legislation for Aboriginal children can be applied to the child. You should also let the Helpline know who is in the family. This does not only mean the members of the household, but also any extended family or kin that you are aware of.

Sometimes you may not have all of this information. At a minimum, DCJ needs to have enough information to help identify and locate the child or class of children who are reported to be at ROSH.

You can also gather further information to inform a report by engaging with the child and related services, and/or exchanging information with other organisations working with the child and their family. You are permitted to do this under Chapter 16A of the Care Act if the other organisation is a prescribed body and the requirements of Chapter 16A are met.

Non-English speaking reporters

Reporters requiring the assistance of an interpreter can contact the Translating and Interpreting Service (TIS National) on 131 450. The service covers more than 150 languages.

The NSW Health Care Interpreter Service offers free, confidential and professional interpreters for patients, their families and carers who do not speak English as a first language or who are Deaf when they use public health services.

More information is available at:

Safeguards for reporters

Section 29 of the Care Act provides protections for people who make reports to DCJ, a CWU, or to a person who has the power or responsibility to protect the child or class of children. Reports to the Helpline are confidential and are only shared with other agencies when this information sharing is permitted by law.

The reporter’s identity (if known), or information from which the identity of that person could be deduced, cannot be disclosed except with the:

- consent of the person

- leave of a court dealing with proceedings relating to the report.

There are also exceptions for disclosing a reporter’s identity to law enforcement agencies in very limited circumstances (section 29(4A), (4B) and (4C)).

If a report is made in good faith, reporters are protected from liability for defamation, and civil and criminal liability.

The making of a report does not constitute a breach of professional ethics or amount to unprofessional conduct.

Reporters are protected against retribution for making, or proposing to make, a report (section 29AB).

Reporting child abuse to the police

In addition to the mandatory reporting requirements in the Care Act in relation to child protection reporting, there are provisions with the Crimes Act 1900 that relate to reporting child abuse to the police.

Subject to section 316A of the Crimes Act 1900, all adults in NSW who know, believe or reasonably ought to know that a child abuse offence has been committed, and fail to report the information to the police as soon as it is practicable, are guilty of an offence.

However, if you make a report to DCJ via the Helpline or CWU, your responsibility to make a report to the police is met. A person will not be guilty of an offence if they have a reasonable excuse for not reporting the information to police. This includes knowing or reasonably believing that:

- The information has already been reported under mandatory reporting obligations, such as to the Child Protection Helpline, a CWU or to the Office of the Children’s Guardian under the Reportable Conduct Scheme, or the person believes on reasonable grounds that another person has reported it.

- The information is already known to police.

- The alleged victim is an adult at the time of providing the information and doesn’t want it reported to the police.

- There are grounds to fear for their safety or another person’s safety if they report to police.

In addition, the person has a reasonable excuse for failing to notify the police if they were under 18 years of age when they obtained the information.

It is also an offence if an adult working in an organisation that engages adult workers in child related work knows another adult working there poses a serious risk of abusing a child, and they have the power to reduce or remove the risk by virtue of their position in the organisation and they negligently fail to do so (section 43B of the Crimes Act 1900).

Responding to child wellbeing and safety concerns

What happens when a report is received by DCJ?

Reports received by DCJ are assessed by practitioners to determine whether the information meets the ROSH threshold.

When a report is assessed by the Helpline as reaching the ROSH threshold, it will be forwarded to a Community Services Centre or the Joint Referral Unit for further assessment in circumstances where the report appears to include allegations of sexual abuse, serious physical abuse or serious neglect.

Information about how DCJ assesses and responds to reports is included in Chapter 7.

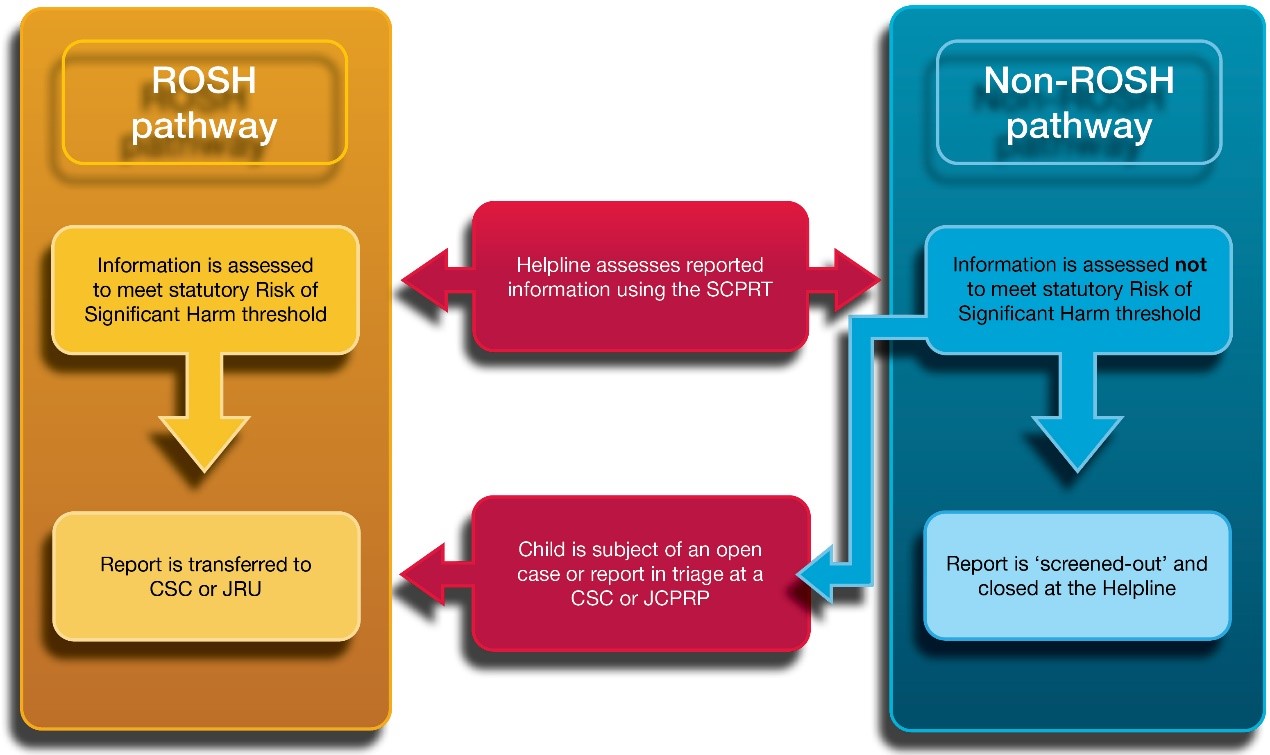

The diagram below shows this process.

A text alternative to the Reporting Pathway diagram is available.

Feedback to mandatory reporters

The Helpline aims to provide written feedback to mandatory reporters who have made a report via phone.

Reporters who have made a report via the ChildStory reporter website are able to obtain status updates about the progress of their report via the ChildStory community portal.

The e-report feedback will include details on whether a report about a child met the statutory ROSH threshold and the assessment outcome.

What else can reporters do to support families?

Supportive interventions to reduce risk to the child are encouraged and not prevented by the making of a report. This is embedded within section 29A of the Care Act. Consider alternative sources of support to assist families who would benefit from accessing support to address their current circumstances. Some of the steps you might take are outlined below:

- Support the child yourself within your role - Consider what additional steps your service can take, including whether your service is best placed to discuss your concerns with the family and whether your service can offer to provide additional interventions or change your current interventions to further address risk factors.

- Find other supports for the child and their family - Explore appropriate support services for the child and their family. The following options may assist you:

- If you work within an agency that has a Child Wellbeing Unit, they can be called to get advice about referral pathways. Call Health CWU on 1300 480 420, Police CWU on 131 444 or Education CWU (private number). Staff within these agencies can also contact their CWU via eReporting through the Mandatory Reporter Guide.

- Contact your local Family Connect and Support if you would like help referring the family or child to local support services such as housing or respite services.

- Visit the Human Services Network website to access a broad range of services.

- Education staff working for non-government schools should contact the Association of Independent Schools or Catholic Schools NSW. Catholic system reporters can seek assistance from their Diocesan office or local Catholic schools authority.

- Sharing information with other practitioners - The key principles of information sharing recognise the importance of collaboration, and that agencies with responsibilities relating to the safety, welfare or wellbeing of children should be able to share relevant information.

Chapter 16A of the Care Act allows exchange of information relating to a child or young person’s safety, welfare or wellbeing. This applies whether or not the child or young person is known to DCJ, and whether or not the person to whom the information relates consents to the information exchange.

Further information about information sharing is available in Part 4 and on the DCJ website - Document your client contact - Document all client contact in accordance with your organisation’s policy and procedures.

Practice advice and resources

Understanding trauma and resistance

When a person experiences persistent fear, terror and feelings of helplessness, they can experience trauma. The causes can be physical, sexual, emotional or psychological abuse, or exposure to domestic violence or neglect.

When reporting and responding to child wellbeing and safety concerns, it is important to remember that families who are involved in child protection or out-of-home-care work may have experienced trauma.

Considering the concerns you have for a child’s safety and wellbeing in the context of possible trauma may help you to view the responses and actions of the child and their parents differently.

When reporting and responding to safety and wellbeing concerns, it is important we are transparent and inform parents of our role and actions wherever possible.

Understanding vicarious trauma

Vicarious trauma is the transfer of trauma that can occur through engagement with those who have experienced trauma. This is a risk for all practitioners working with children and families who have come into contact with the child protection system in NSW.

If practitioners feel emotional or impacted in the course of their work, they are encouraged to contact a support person to discuss their personal experiences in a helpful and constructive way. These support people may include:

- a supervisor

- a workplace health and safety officer

- private counsellors

- a general practitioner

- the Employee Assistance Program

Responding to a disclosure of abuse

Since disclosure from a child is a significant event in their life, it is important that we listen, be engaging and show our support. We know that disclosure takes time and is not always a straight forward disclosure, but may be communicated in various ways, such as through a change in behaviour. For many children, disclosure is a process. Your role is to listen when children tell you about what is happening in their lives. The role of the person hearing a disclosure is not to interview or gather evidence. This is the responsibility of DCJ practitioners and/or police officers.

It is appropriate for a person hearing a disclosure to clarify information provided by the child, but they should not add information to the child’s story or ask leading questions. For example, it can be extremely helpful before completing an MRG to know the relationship between the child and alleged ‘perpetrator’ and when they are likely to see that person next.

You should respond to a disclosure by being calm and listening carefully. Let the child tell their story freely and in their own way. Acknowledge how difficult it may have been to disclose and reassure the child that telling someone what happened was the right thing to do and that you believe them.

Children who have experienced abuse need us to notice their distress, recognise when they are telling us about the abuse, and show them that we are interested, concerned and capable of listening to their story.

As soon as possible after hearing a disclosure, it is important to document the information you heard, as close as possible to the child’s exact words, so you are able to provide that information to DCJ and/or the police as needed.

Additional resources are available at:

- The National Association for the Prevention of Child Abuse and Neglect

- Bravehearts

- Office of the Senior Practitioner, Child Sexual Abuse and Disclosure Literature Review

Focus on the experience of the family

Your focus should remain on how the child is experiencing the parental or carer behaviours, their particular risk and protective factors and any ROSH. The obligation to report current concerns exists regardless of a parent’s remorse or their stated intention to seek help.

It is important to suspend personal judgments or assumptions when considering child safety and wellbeing.

Working with Aboriginal families and communities

When reporting and responding to safety and wellbeing concerns, it is important to understand the history of colonisation and traumatisation of Aboriginal people as a result of previous Australian Government policies, legislation and actions. The effects of trauma are intergenerational and continue to impact Aboriginal people today. Due to previous policies and legislation in Australia, Aboriginal people were disempowered, disenfranchised and not allowed to participate in decisions that involved themselves, their children or their families. It is important that we do not repeat these mistakes when working with Aboriginal families and communities today. It is important to be respectful, sensitive and work in partnership with Aboriginal families and communities. All work with Aboriginal families must prioritise Aboriginal children’s cultural permanency.

Working with culturally and linguistically diverse families (including migrant and refugee families and asylum seekers)

Culture and experience influences parenting practices. While it is important to recognise and respond to the influences of cultural factors, it is critical that harmful or neglectful behaviours are not labelled and dismissed as 'cultural practice'. A focus on the impact of the behaviour on the child is your priority.

It is important to note that cultural practices that seem different or unfamiliar but do not place the child at suspected ROSH should not be reported but responded to in a way which aims to address the level of risk and increase supports. Wherever possible, ask parents/carers if they wish to use translators where English is their second language.

Working with people with a disability

Disability is any condition or impairment that impacts a person's daily activities or communication. Some children may experience more than one disability and some conditions can lead to others.

There are many different kinds of disability and they can result from accidents, illness or genetic disorders. A disability may affect mobility, ability to learn things, or ability to communicate easily, and some people may have more than one. A disability may be visible or hidden, may be permanent or temporary and may have minimal or substantial impact on a person’s abilities.

Types of disability

As described by the Australian Network on Disability, the impairments and medical conditions outlined in the Disability Discrimination Act, include:

- Physical —affects a person's mobility or dexterity.

- Intellectual —affects a person's abilities to learn.

- Mental Illness —affects a person's thinking processes.

- Sensory —affects a person's ability to hear or see.

- Neurological —affects the person’s brain and central nervous system.

- Learning disability

- Physical disfigurement

- Immunological —the presence of organisms causing disease in the body.

See more at Raising Children Network’s Guide to Disabilities.

Disability is more than just a health issue. A child's experience of disability is a combination of their age, developmental stage, how they experience their mind and body, and the society they live in. Part 3 provides further advice and resources for engaging with children with a disability, including ensuring children with a disability are afforded all rights and opportunities to participate in decision making.

Not all children with disability will identify as having one. Use the language they use to describe their experiences. Some children will act out rather than be seen as having a mental illness or intellectual disability.

Various cultures may have beliefs about disability. Seek cultural consultation to help you explore beliefs and understandings of disability with the family.

It is not the child’s disability that creates a barrier to their participation —it is our society that does. Consider how you change environments and communication styles to create equity for people with disability. For more information see Social model of disability.

Parents with a disability may experience additional parenting challenges and barriers in accessing support. When reporting and responding to safety and wellbeing concerns for children with a parent who has a disability, it is important that we don’t further compound the barriers and judgements faced by the family. Working with parents who have a disability requires a creative and flexible approach without the burden of labels and assumptions, particularly about the experience of a child or the parent. Ensure that staff take the time necessary to listen and understand what the issues parents with a disability are experiencing.

Supporting a positive gender and sexuality identity

All children, including those who may identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, intersex, queer/questioning and other diverse sexual orientations and gender identities (LGBTIQ+), have a right to:

- be safe

- live in accepting, supportive and caring homes

- be treated as an equal member of a family and a community.

It is important to support a child who identifies as LGBTIQ+ by respecting and accepting them as they are, providing age appropriate information about available services, support, events and celebrations.

Parents and carers who identify as LGBTIQ+ also have the right to be treated with respect and as equal members of a family and community.